Wednesday, June 12, 2019

I turned my old Android phone into a web server. Here's how.

I got tired of paying nearly $80 per month for my one phone line and the less than one gigabyte of data I was using. Logging into my Verizon Wireless account to look for a better deal, I found that the "recommended plan" for me was one that costs even more money and allows five times more data.

After a little bit of research, I decided to try Google Fi. The only problem was that my aged Verizon-provided Droid Turbo does not support Google's networks. However, seeing that I would stand to be paying just under $30 a month with Google, it didn't bother me to buy Google's cheapest offering, a new Moto G6 for $100.

It was super easy. I didn't even have to call Verizon (later on I did anyway, just to make sure). Google has this sorcery where you give them your Verizon Wireless credentials and they transfer and cancel things on your behalf.

Anyway, new phone works, all is well. But what about this old phone? It's practically unsellable, though it works just fine.

To be more specific, the Droid Turbo has the following specifications (according to wikipedia):

That's a pretty powerful computer. Also, if this study on the power consumption of a comparably more powerful phone is applicable, then with the phone's mobile network radio and screen turned off, it will draw less than one watt of power. For comparison, a desktop computer might draw between 60 and 300 watts. This is peanuts compared to the Flux Capacitor's minimum requirement of 1.21 gigawatts, but that's another matter.

I have an idea! Let's gain root access to the operating system underlying the phone, wipe over that system with some Linux distribution having drivers appropriate for the phone, install a web server on it, and expose it to the internet! Wouldn't that be fun?

No, it would not be fun. It's not even possible, because Verizon is evil.

I'm well out of my depth on this subject, but as far as I understand from reading on the internet, when a phone powers up, there's a little system that loads a program that starts up another little system that loads a program that etc., etc. until the "real" operating system is loaded and starts running your beloved apps.

At each stage in this process, or at at least one stage, the code whose job it is to further the loading of the system can check whether what it is loading is "legit," for some definition of legit. Qualcomm even makes a special circuit that's effectively "write-once" memory, so that you can potentially modify such logic (e.g. to say "don't check whether it's legit") but can never change it back.

Many phones that reach the consumer as part of a wireless service contract (such as my old one) have their "bootloader locked" so that the "ROM" loaded to start the system must have a certain digital signature. This means that you can't do anything with the phone except view advertisements and buy merchandise. Were you to replace the contents of the ROM with anything else, the phone would refuse to start, or perhaps permanently disable itself so that you can never do anything with it again (called "bricking," apparently because at that point the phone is little more than a silicon brick).

Fortunately, phone manufacturers are not, on the whole, in the business of limiting the capabilities of their products, and so Motorola Android phones have a process you can use to "unlock the bootloader," typically voiding the phone's warranty in the process.

This involves turning off the phone, turning it on in a special way (holding the power button and the volume-down button), copying down some magical numbers, and typing them in to one of Motorola's websites. Then, supposedly, Motorola looks up some secret key based on what you typed, and then you can enter that key into your phone and, voila! From then on your phone will load whatever happens to be in memory, digital signature be damned.

Except that it doesn't work if you got your phone from Verizon. The website will tell you that "your phone cannot be unlocked." Why? Because Verizon insisted on this. Because Verizon is evil.

This phone does not belong to you, it belongs to us. We have no more use for it, and so neither shall you.

Ok, so it's disappointing that I can't completely control the system on the old phone, but not all is lost. After all, Android is designed to make writing apps easy. I could just code up my hobby as an application, rather than having to replace the entire system.

In fact, I don't necessarily need to write any code. Surely somebody has already released an Android app that makes the phone serve web pages. So, I can just download such an app from the Play Store, configure it to serve my static website, and job done.

Where's the fun in that? I want the full Linux experience. Fortunately for me, there's an option. It's called UserLAnd. These wizards have leveraged a program called proot, which allows you to "chroot, mount --bind, and binfmt_misc" without root privileges. proot uses a Linux feature called ptrace to trick a running program into thinking that it's running as root in a chroot jail, when in fact it's just being controlled by proot.

The folks at UserLAnd wrapped up proot in Android app clothes, including a terminal emulator and busybox, a compact suite of Unix tools, including, conveniently enough, a simple HTTP server.

Once you have UserLAnd installed on your phone, you can instruct it to install a Linux distribution in the proot jail, then start a "session" on that system as a specified user with a specified password, and you're ready to go.

Working on the Linux command line using a phone is awful. The first thing I did is find out which ssh server was running on my new system and connected to it from my laptop. This involved me learning properly for the first time how to use ssh-keygen, ssh-copy-id, and ssh-agent. Also, apparently dropbear exists and is an alternative to sshd.

The result is that I can now poke around inside my old phone from my laptop. For example:

david@LAPTOP-DTKG66RE:~

$ ssh -Y david@192.168.1.4 -p 2022

Warning: No xauth data; using fake authentication data for X11 forwarding.

david@localhost:~$ ps -ef | head

UID PID PPID C STIME TTY TIME CMD

david 6995 10263 0 Jun12 ? 00:00:00 dropbear -E -p 2022

david 6996 6995 0 Jun12 pts/0 00:00:00 -bash

10133 7136 424 0 Jun12 ? 00:00:19 com.google.android.inputmethod.latin

10082 9923 424 0 Jun11 ? 00:00:00 com.vzw.apnservice

10004 9970 424 0 Jun11 ? 00:00:00 com.android.providers.calendar

10006 9985 424 0 Jun11 ? 00:00:03 android.process.acore

10055 10005 424 0 Jun11 ? 00:02:11 com.google.android.gms

10055 10018 424 0 Jun11 ? 00:00:17 com.google.process.gapps

10085 10068 424 0 Jun11 ? 00:00:05 com.telecomsys.directedsms.android.SCG

david@localhost:~$

Alright! Now all I needed to do is:

sudo apt install git,git clone http://github.com/dgoffredo/dgoffredo.github.iocd dgoffredo.github.iomakebusybox httpd -p 0.0.0.0:8080Now my phone is serving my blog at port 8080, but how do we access it from the internet?

When you type an IP address into your web browser, the browser attempts to establish one or more TCP connections to that address on port 80. But I'm not listening on port 80, I'm listening on port 8080. This is because you can't bind to ports below 1024 unless you are root. Besides, even if I were listening on port 80, it's my home wireless router that's getting the incoming connection. How is it to know that it is meant to forward that connection to my old phone?

Fortunately, the Netgear WNDR3400v3 wireless router sitting by my window supports something called "port forwarding," which allows you to say "when you receive a connection on port X, instead forward that connection to local address Y on port Z."

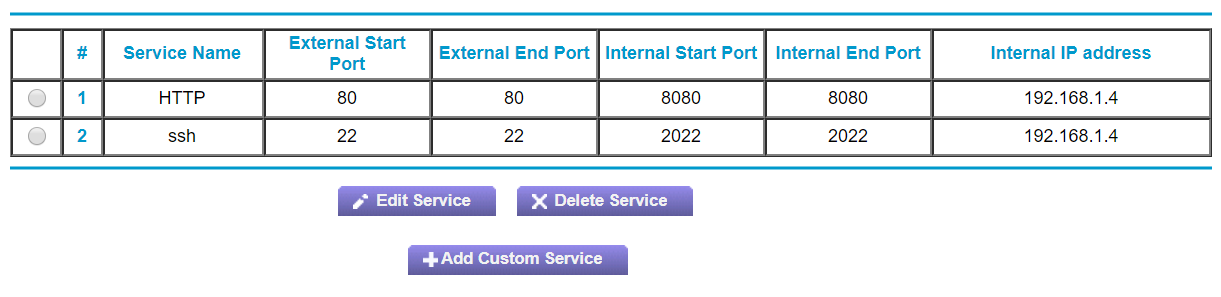

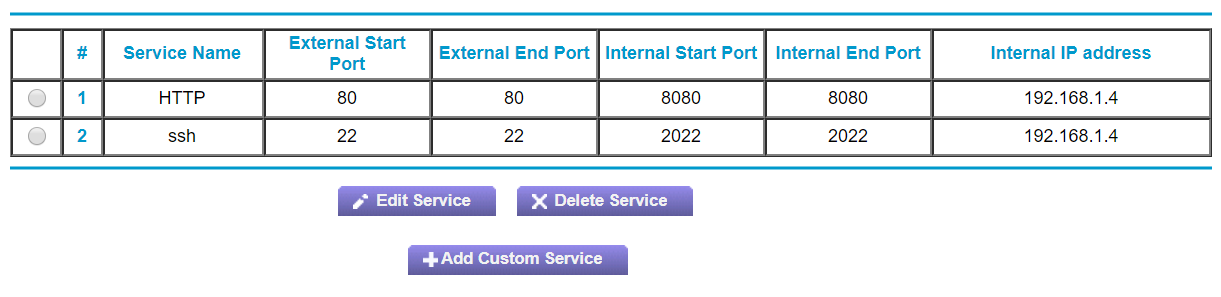

So, I navigated to my router's admin web interface at http://192.168.1.1, and

configured the following settings:

192.168.1.4 is the local address of my old phone, which is connected to the

router over Wi-Fi, port 80 is the port on which I can expect HTTP requests to

enter my network, and port 8080 is the port on which my phone is listening.

You'll notice I also configured forwarding for ssh, so that I (or, now that I've written this, almost anybody) can remotely log in to my old phone. Remember, though, that the system to which I'm logging in is just a proot jail running inside of an Android app having no special permissions. I suppose you could erase my SD card, which would be a dick move, but since I just reset the phone there isn't anything on it to lose. Go ahead and add my phone to your botnet, see what I care!

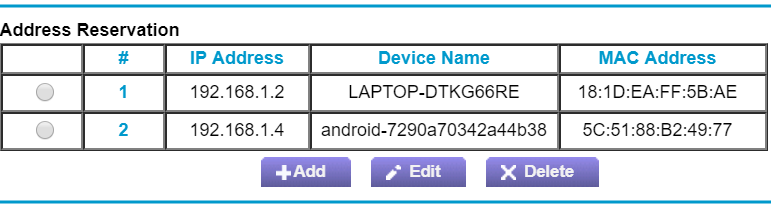

In addition to telling my router to forward HTTP requests to my phone, I also

need to tell it always to assign the local IP address 192.168.1.4 to the

phone. Otherwise, the next time I restart the phone or the router, the phone

might be assigned a different local address (e.g. 192.168.1.5). The router

has another option for this, called "address reservation."

This says that any device having my laptop's MAC address

(which is just my laptop) will be assigned local address 192.168.1.2, and any

device having my old phone's MAC address will be assigned local address

192.168.1.4. So, that settles that.

At this point, the old Android phone sitting in my apartment and connected to my Wi-Fi router is now accessible from the entire internet at 74.68.159.94, my router's public IP address.

"Seventy-four, sixty-eight, one hundred fifty-nine, ninety-four" does not have much of a ring to it, I admit. Sure, it's kind of like a weird phone number that you could memorize, but who wants to do that?

It would be better if that address could be looked up somewhere using an alternative name -- a more human-friendly name.

Fortunately, such a system exists. It's called the Domain Name System (DNS), and, luckily enough, there are people who own domain names and are willing to let you use a subdomain of theirs for free!

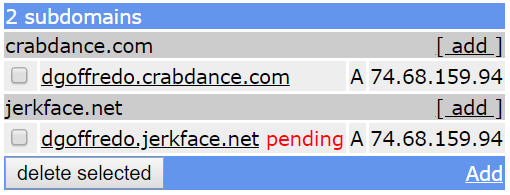

The service I used is called freedns.afraid.org.

Using this, I was able to associate the subdomains

dgoffredo.crabdance.com and

dgoffredo.jerkface.net with my public IP,

74.68.159.94. So, when you type either of those names into your web

browser, the browser will ask DNS "what IP address(es) is (are) associated with

this domain?" DNS will reply "74.68.159.94," and then the browser will send

an HTTP request to the old Android phone sitting in my apartment.

FreeDNS's web interface looks like this:

That service even has a programmatic API, so in principle I could carry around my web server it my pocket, and every time it entered a new network and was assigned a new IP address, it could notify DNS of the new address, so that my website remained available anywhere my old phone happened to be connected to the internet. Besides being a useless idea, it wouldn't even really work, though, because I wouldn't be able to set up port forwarding on every network that I enter.

I have no answer.

After all, I don't need to host my blog from an old phone sitting in my apartment. It's already hosted "in the cloud" at dgoffredo.github.io. Instead, this was just for fun.

It got me thinking, though, about how we all have these powerful computers in our pockets, connected to the internet, all day, every day. Further, whenever you're asleep at night, the phone is plugged into a power source, screen off, still connected to the internet.

I looked into the idea of a distributed only-when-you're-sleeping volunteer computing network, so that scientists could crunch the hard numbers on protein folding and quasar searching and whatever else, at no cost to you except the additional pennies in electricity that your phone would consume while you sleep.

This already exists, of course. It's called BOINC and there's an Android app for it that does exactly what I described. It's now installed on my old phone server, chewing up CPU cycles looking for possible signals in LIGO's gravitational wave detection data.

So, hack around with your phone! It's fun, and you might learn something.